16 June 2025

What role does the infant gut microbiome play in shaping the developing immune system? A crucial one, says Associate Professor Timothy Hand, who recently shared his research investigating this relationship at the Malaghan Institute.

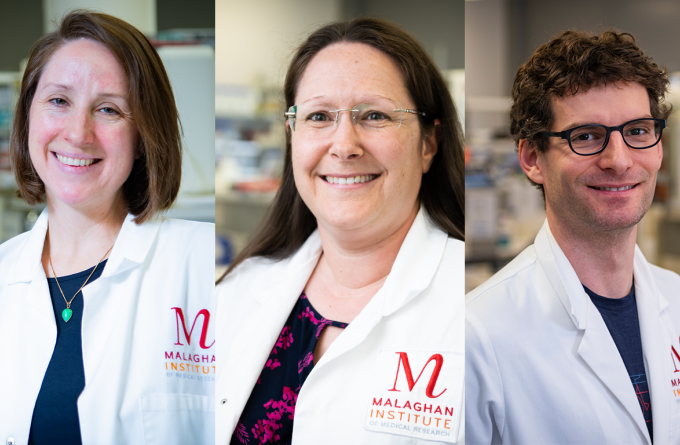

Dr Lisa Connor with Associate Professor Timothy Hand at the Malaghan Institute

Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA delivers more than 11,000 babies each year.

"That’s about three births an hour, every hour, for 365 days a year," says the Associate Professor of Paediatrics and Immunology at the University of Pittsburgh.

With that many babies, there is no shortage of used nappies. Fortunately for A/Prof Hand’s research group, that is exactly what they are looking for. They work closely with the hospital to collect used nappies, which most new mothers are happy to hand over, even if they are a little confused about why anyone would want them.

A/Prof Hand is investigating how our immune system is shaped by our early microbiome.

“We collect faecal samples from these used nappies and at several time points in the infant’s early life and sequence the DNA. This allows us to map which bacterial species colonise the gut in these initial days, months and years of life,” says A/Prof Hand.

Every adult is colonised by trillions of diverse bacteria, viruses and fungi. These microbes constitute our microbiome and have coevolved with us. They serve several essential functions like helping with digestion, keeping out potentially harmful microbes and even helping regulate our immune system.

An average human adult has approximately 100 trillion bacterial cells in their microbiome, that means there are more cells in our microbiomes than all the cells that constitute the rest of our bodies.

“When babies are born, they are essentially sterile. By mapping newly colonising bacteria and which antibodies arise in the infant immune system, we can work out the relationship between the developing immune system and our microbiome."

Several factors determine how the gut microbiome and immune system develops in these early years of life.

“Breastmilk is a major source of antibodies in early life. Breastmilk contains a range of antibodies that helps defend the infant, helping block the growth of harmful bacterial populations.”

Mothers ingest bacteria, virus and fungi through their diet. Once this gets to the digestive tract, it activates a type of immune cell called B-cells in the small intestine. These B -cells then produce antibodies that defend against specific bacteria. The antibodies then migrate to the breast via the blood stream and are transferred to the child through the milk, providing protection and reducing the likelihood of developing disease.

Another factor that plays a significant role in the development of the microbiome and the immune system is premature birth.

One of the patterns A/Prof Hand and his group have discovered by characterising the early microbiome of infants is that pre-term babies tend to have a different progression of bacteria than babies born full term.

“Changes in the bacterial population takes longer in pre-term babies. We don’t know why this is.”

One reason may be that immune cells still behave as if they are in the womb trying to detect infections present in the amniotic fluid, hence indiscriminately killing off more populations of bacteria that establish themselves in the gut.

Some pre-term infants, usually born between 24-34 weeks in the womb, develop a dangerous condition called Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) where tissues in the infant’s gut becomes inflamed and damaged. This can be life-threatening and may mean the damaged tissue has to be surgically removed. This leaves the infant with a shorter digestive tract which can have long-term complications, potentially for the duration of the infant’s life.

“One of the questions we are trying to answer is if this condition can be detected early in the infant’s life so drastic measure like surgery do not have to be used,” says A/Prof Hand.

“We’re looking to understand if there are indicators in the developing microbiome that points to infants at risk of developing NEC.”

A/Prof Hand and his team are developing new techniques to map and quantify bacteria and antibodies that have wide ranging applications for researchers investigating the gut microbiome, including at the Malaghan Institute.

He visited the institute as one last pitstop on his down under tour, having presented his research as a guest speaker for the Mucosal Immunology and Microbiome Symposium in Queensland, Australia recently.

Related articles

Dr Kerry Hilligan awarded Sir Charles Hercus Health Research Fellowship

2 December 2025

New funding supports cutting-edge research into immune cell metabolism

13 October 2025

Malaghan visiting researcher: Dr Johanne Jacobsen

22 July 2025

Te Pūnaha Awhikiri: Exploring the Immune System through Mātauranga Māori

7 July 2025

Dr Michelle Linterman: Asking the age-old question

30 April 2025

Malaghan visiting researcher: Dr Ian Myles

2 April 2025