18 December 2025

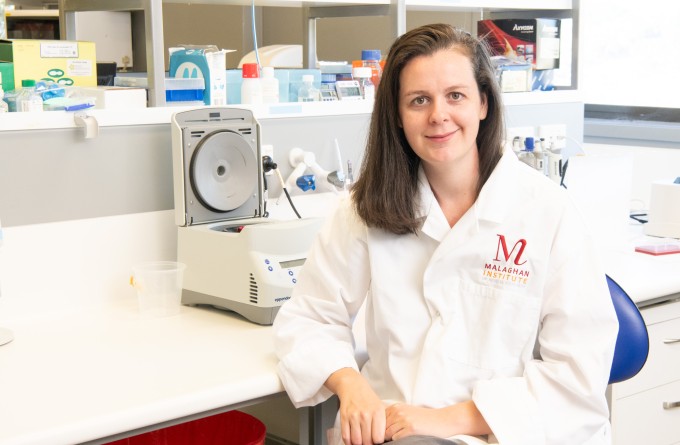

Dr Kit Moloney-Geany is investigating one of the immune system’s oddities – tiny lymph node-like structures that pop up in response to inflammation and may hold important clues to how we fight disease.

“My research focuses on how immune cells within the lung organise themselves into structures known as tertiary lymphoid structures,” says Kit, who works in Dr Kerry Hilligan’s Lab at the Malaghan Institute. “They share many similarities to lymph nodes, helping drive adaptive immune responses within the lung tissue. Our interest is on how these structures form and what influence they have on disease outcomes.”

Tertiary lymphoid structures are small clusters of immune cells that form in tissues outside the lymph system – where B-cells and T-cells are called in and put to work. This is unusual, as typically the coordination of B- and T-cells takes place within lymph nodes – designated sites around the body like the armpit, groin or neck that act as coordination hubs for immune responses.

Whenever there is damage to cells, whether by bacteria, virus or other assault, we see inflammation – the first step in overcoming any threat. And where there is inflammation, we find tertiary lymphoid structures forming like barnacles on a ship.

“Tertiary lymphoid structures can form wherever there is tissue inflammation. This means they have been identified in cancer, infections, autoimmunity and allergy. Our lab focuses on their formation during influenza A infection and aspergillus fungal infection.

“For influenza, tertiary lymphoid structures form due to the excessive inflammation caused by the virus infecting and damaging airway cells in the lung. It is less clear how they form during fungal infection and is an area of active research for our lab.”

Like many parts of the immune system, there is a duality to tertiary lymphoid structures. On the one hand, they may help overcome disease, but in other contexts they can also inadvertently sustain it.

“The role of tertiary lymphoid structures in disease is complex. For infections and cancer they are often seen to be good, helping to clear infections faster and facilitate anti-cancer immunity. In autoimmunity they are viewed as bad as they are sites for continued inflammation and auto-reactive immune cells.”

One of this biggest questions surrounding tertiary lymphoid structures is why do they exist? Our lymphatic system is better-equipped to remove harmful microorganisms in a short span of time. In fact, by the time a tertiary lymphoid structure forms, it’s likely the rest of the immune system has done its job and the infection has already been cleared.

Yet, tertiary lymphoid structures persist long past infection, the cells they recruited hanging out in the surrounding tissue for weeks or months.

Tertiary lymphoid structures are found across the animal kingdom, not just in humans, suggesting they play an important evolutionary role that science has yet to fully grasp. Kit explains that rather than one system superseding another, they may both work in their own ways to protect us from disease.

“The lymphatic system and tertiary lymphoid structures seem to work independently from each other but perform the same role. That role is to generate highly-specific immune responses towards an infectious agent. That can mean many things beyond rapidly removing a pathogen like the flu virus.”

While it’s great our bodies can quickly analyse and remove a virus from the lung thanks to our lymph nodes, what happens if that virus returns? It might be a good idea to keep some immune cells around, just in case. That’s where tertiary lymphoid structures come in.

“For tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung, once a B- or T-cell has been generated within the structure, they can migrate and reside within the tissue airways and air sacs. They then remain there and can be activated again if the same pathogen enters the body, thereby providing immunity similar to what is generated by vaccinations.”

Perhaps one way to think about the relationship with tertiary lymphoid structures and lymph nodes is boots on the ground versus command central. Both are working to fight the threat, they’re both reliant on working together, yet they go about it differently.

For tertiary lymphoid structures, it’s their proximity to the site of infection that makes them valuable, keeping the site alert and primed to rebuff a subsequent infection.

Tertiary lymphoid structures may also be the reason we tend not to get sick from multiple infections at once. One of the main research goals of the Hilligan Lab is to look at how past infections shape and inform future responses, and tertiary lymphoid structures might be pivotal. By recruiting immune cells to the site of infection, training them, then keeping them there long after the infection has cleared, that region of the body remains better equipped to repel any other threats.

“Tertiary lymphoid structures impact disease in a multitude of ways,” says Kit. “For subsequent infections, it is believed that they act as ‘landing spots’ for immune cells to activate faster than normal, resulting in enhanced immunity. They also retain many different immune cells that can regulate inflammation. As such, they may reduce the severity of infections by ensuring the lungs do not get too damaged.

“My hope is that by understanding how tertiary lymphoid structures form we can develop more precise immunotherapies across a broad range of diseases.”

“Conversely, in situations where we don’t want to activate immune cells, such as autoimmunity or allergy, tertiary lymphoid structures can exacerbate these conditions by providing an environment for continuous activation. In all instances, there are still many unknowns that need to be answered, making it an exciting area of research.”

However, figuring out exactly what goes on in tertiary lymphoid structures, how they’re formed and how they contribute to long-term protection is a challenge. What makes these structures unique is their positioning in the tissue and how the cells they recruit are ordered. Traditional means of studying the immune system – essentially taking biological samples, blending them up then sifting out the immune cells – won’t work. A holistic approach is needed – looking at the system as a whole rather than individual components.

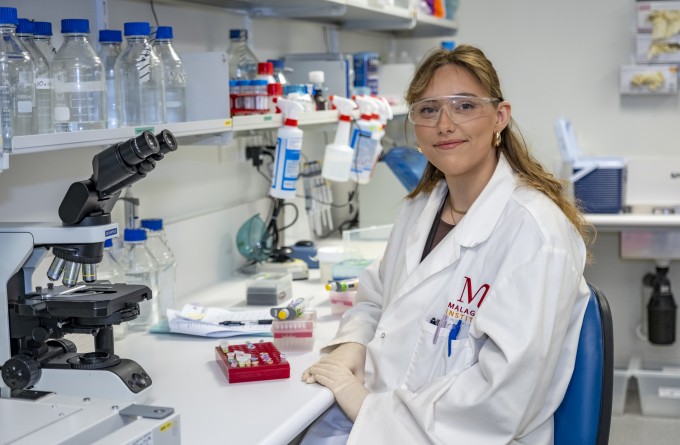

In order to study tertiary lymphoid structures, Kit has been combining cutting-edge, multi-disciplinary analytical tools to build up piece-by-piece an understanding of what’s going on.

“Immune cells are incredibly dynamic, and their function is often influenced by cell-to-cell contacts – who’s talking to who. My work combines microscopy, flow cytometry and spatial transcriptomics to get a picture of what’s going on,” he says.

“As many different immune cells reside within a tertiary lymphoid structure, I’m interested to understand what they are saying to each other and how that influences their function. Having them within the lung and located close to the airways directly impacts how our body responds to inhaled bugs or particulates and how fast they respond. To dig into this question we have developed new tools that enable us to isolate cells residing in these structures from the rest of the lung.”

Kit undertook his PhD at the University of Otago under the supervision of Professor Parry Guilford, focusing on designing and improving non-invasive cancer diagnostic tests. He joined Malaghan in 2024 to research ways we can harness tertiary lymphoid structures to better prevent or fight disease.

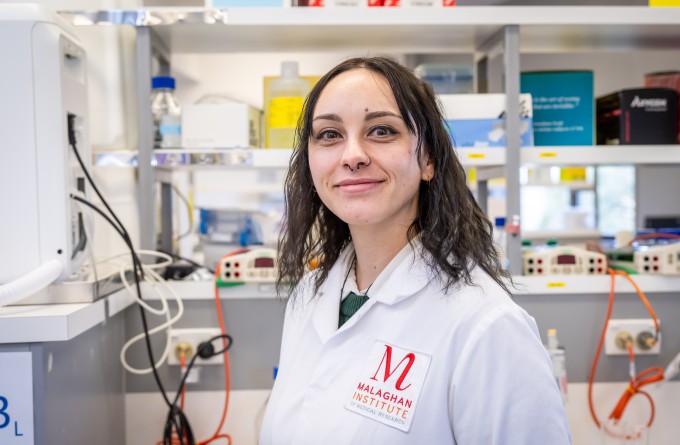

“My tenet for science has always been about translating research to improve health. During my earlier research I would often see tertiary lymphoid structures in the tumours that I analysed. It made me interested in the immune system, especially as the presence of these structures correlates strongly with patients that respond to immunotherapies like checkpoint inhibitors.

“I’ve always been interested in understanding how different cell types within the body – both structural and immune – communicate to generate immunity. As I learnt more about tertiary lymphoid structures it became clear that they are an integral part of many diseases and immune responses, yet so much remains to be known about them.

“My hope is that by understanding how they form we can develop more precise immunotherapies across a broad range of diseases.”

Related articles

Momentum is everything: advancing CAR T-cell research for future trials and treatments

25 February 2026

NZ-UK research deepens understanding of germinal centres for better vaccine design

27 January 2026

The nose knows: new research explores next generation of nasal vaccines

2 December 2025

Tracking the journey of the shapeshifting bacteria behind stomach cancer

19 November 2025

Marsden funding to drive discovery and innovation in cancer, allergy and infectious disease research

5 November 2025

How our immune system tackles fungal foes

23 October 2025