29 August 2022

A collaboration between the University of Auckland's Auckland Cancer Society Research Centre (ACSRC) and the Malaghan Institute aims to address Aotearoa’s leading cause of cancer death by improving immunotherapies that target lung cancer.

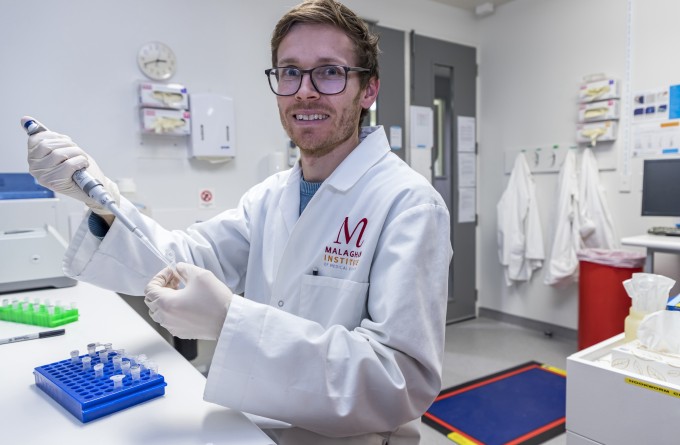

Dr Regan Fu, left, with Professor Ian Hermans. Dr Fu will be working on screening the different hypoxia-activated immunostimulants at the Malaghan Institute to determine which potential candidates might be suitable for clinical trials.

More than 1000 Kiwis die from lung cancer each year according to Lung Foundation NZ Tupapa Pūkahukahu with survival rates well below international norms. Māori are 3.5 times more likely to die from the disease than non-Māori.

Funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Maurice Wilkins Centre for Molecular Biodiscovery, the collaboration aims to create new immunotherapeutic tools or stimulants that boost the effectiveness of existing anti-cancer immunotherapies, improving overall patient response rates to this disease.

“Lung cancer has a large inequity in health outcomes for Māori” says ACSRC Associate Professor Adam Patterson, who is leading the research. “Although immunotherapies like immune checkpoint inhibitors are on their way, experience from overseas indicates only about 10-30% of patients respond, so there is significant room for improvement.”

“We’re developing novel adjuvants or immune stimulating agents that would potentially make lung tumours more responsive to immunotherapies like checkpoint inhibitors” says ACSRC lead medicinal chemist Associate Professor Jeff Smaill. “Studies to confirm this are being undertaken at the Malaghan Institute, with the aim of identifying a lead candidate to move forward into clinical trials in the near future.”

The Malaghan Institute’s Professor Ian Hermans says the aim is to make the site of the tumour more immune-responsive. “There are immune cells in and around tumours, but their activity is suppressed which makes them unable to effectively respond to therapy, or to recruit other immune cells to the site.

However, because of their physical structure, solid tumours share properties that can be exploited by researchers to develop ways to help a patient’s immune cells overcome this therapeutic barrier. Hypoxia, or a lack of oxygen, is one such property – a condition brought about partly as a result of the tumour’s dense, rapid growth.

“Through our collaborative efforts we have designed a number of promising candidates that target hypoxic regions.This grant will help evaluate these different candidates so that we can optimise the design to get the best targeting in combination with checkpoint inhibitors.”

For decades, researchers at the ACSRC have been perfecting the design of ‘hypoxia-activated’ drugs that are selectively activated in tumours where oxygen levels are low. This concept is now being applied to an immune-stimulating drug which, when activated in the tumour, will act like an adrenaline shot to nearby immune cells, significantly boosting their activity.

Through this targeting mechanism, the stimulant is only biologically-active in the tumour, and is inactive in healthy tissues which are typically well-oxygenated – ensuring the immunotherapy gets to where it’s most needed. This has the added benefit of lowering any potential related toxicities to healthy tissues making the treatment safer for patients, with fewer side-effects.

“Through our collaborative efforts we have designed a number of promising candidates that target hypoxic regions,” says Professor Hermans. “This grant will help evaluate these different candidates so that we can optimise the design to get the best targeting in combination with checkpoint inhibitor. We’ll also be studying the exact mechanisms behind this hypoxia-activated immunostimulant, to make sure it’s targeting the immune cells in the ways we anticipate and that we more fully understand any potential side-effects or toxicities that may arise.”

Associate Professor Patterson says any New Zealand clinical trial of their lead candidate would focus on strategies to achieve active recruitment and support of Māori participants. But he cautions that it will still be some time before any clinical trials start.

“By the end of the grant we expect to have identified, validated and patent-protected a lead candidate for clinical evaluation,” he says. “If that’s successful, we’d be looking to move forward into human studies, but this can be influenced by many factors along the way and could take several years yet.”

Related articles

Phase 2 clinical trial underway to confirm effectiveness and safety of NZ’s first CAR T-cell cancer therapy

23 July 2024

RNZ Our Changing World: Targeting bacteria, and health inequities

4 July 2024

New clinical research aims to reduce stomach cancer rates and disparities in New Zealand

28 May 2024

A revolution in cancer care is near; here’s what’s needed to make it happen

9 May 2024

Significant milestone reached in first NZ CAR T-cell trial as preparations made for larger phase 2 registration trial

25 March 2024

RNZ: Engineering immune cells to kill cancer

5 November 2023