11 October 2022

Gordon Zhao is developing therapeutic mRNA vaccines for hepatitis B virus infection and liver cancer. The rapid advances in RNA nanotechnology in recent year have opened doors for treating many diseases that have few or no effective therapies.

Gordon is a PhD student in Dr Ian Hermans’ laboratory, a group with a solid track record of developing therapeutic vaccines for diseases including cancer. Gordon’s focus is on hepatitis B virus infection, a disease with minimal long-term therapeutic options that can lead to liver cancer.

“The hepatitis B virus is an ancient virus that has been infecting humans for tens of thousands of years. It has evolved with us, it’s highly adapted to tricking our immune system so it can infect people more effectively,” says Gordon.

A preventative vaccine has been widely administered in New Zealand since 1988, however those infected prior to receiving the vaccine and those who have migrated from countries where the vaccine is not offered can suffer from chronic infection.

“It's like a black box that does seemingly magical things. It’s infinitely complicated and we’re all working to uncover what is behind the smoke and mirrors.”

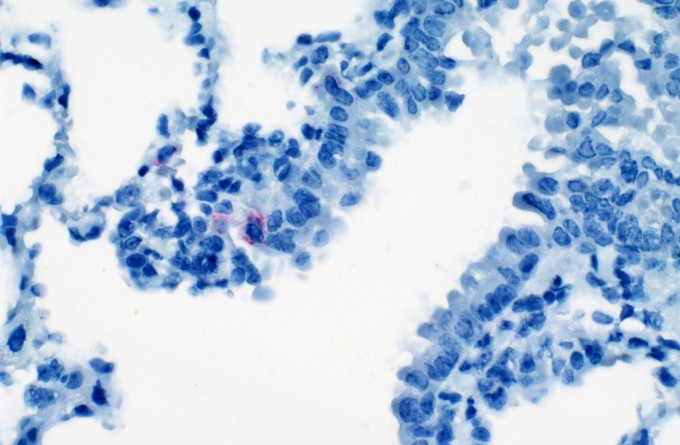

The virus, spread from human to human through bodily fluids, specifically infects liver cells, called hepatocytes. Once it infects the hepatocytes, it rapidly hijacks the human cells’ function to produce its own proteins and make copies of itself.

“One of the most distinct techniques this virus deploys to overcome the human immune system is that it makes a thousand decoys of itself for every complete virus,” says Gordon.

Under the impression that thousands of viruses are present in the liver, the immune system launches a full-scale attack on both the decoys and the complete viruses.

“As you can imagine, this is challenging. For some, their immune systems can effectively overcome the hepatitis B virus and resolve the infection. However, for one in four people, infection becomes chronic - effectively a prolonged battle between the immune system and the virus,” says Gordon.

The liver tissue sits in a state of perpetual inflammation which can lead to damage of the liver cells. The constant infighting causes the immune system to become exhausted and less effective. This high stress environment increases the chances of inaccurate DNA replication when making new cells. This can corrupt the DNA of the liver cells leading to cirrhosis and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma – a form of liver cancer.

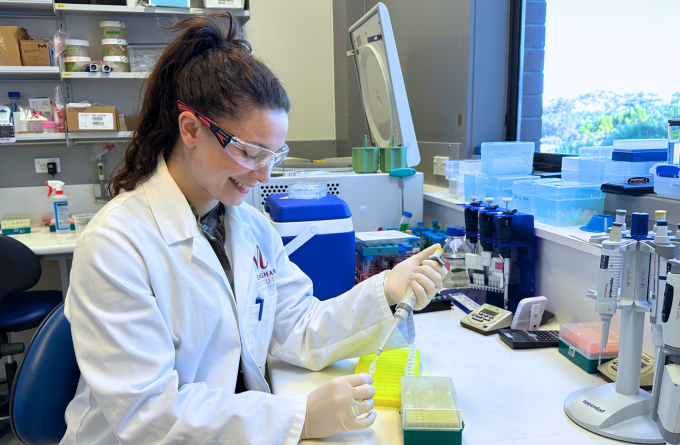

Gordon’s research is focused on developing a therapeutic mRNA vaccine to reactivate the exhausted immune system against hepatitis B virus infection. mRNA vaccines, the technology the COVID-19 Pfizer vaccine was built on, use a molecule called mRNA that contains instructions on how to produce a specific protein. Gordon is synthesising mRNA molecules that signal the body to make certain hepatitis B viral proteins. This mimics the hijacking of the body’s cells by viruses, alerting the immune system and invigorating it into action.

Another unique aspect of this research is to configure vaccines so that they specifically induce immune cells (T cells) to form long-lived populations in the liver. This will not only be important for a therapeutic vaccine for chronic hepatitits B virus infection, where the T cells will kill any infected cells, but will also open up opportunities to design vaccines that induce T cells to kill malignant cells in liver cancer.

“The long-term goal is to develop a therapeutic vaccine for liver cancer where we can administer an mRNA vaccine coding for a protein on the cancer cells that then stimulates long-lived resident memory T-cells that prevent malignant cells from reappearing,” says Gordon.

“Based on earlier work at the institute, it is expected that some unique lipids can be incorporated into our vaccines to encourage T cells to reside in the liver for long periods. It’s like playing with Lego. I switch one part in and another out and it yields different results.”

“One of the things that really attracts me to the immune system is the whole mystery of it. It’s like a black box that does seemingly magical things. It’s infinitely complicated and we’re all working to uncover what is behind the smoke and mirrors,” says Gordon.

Gordon came to the Malaghan Institute after doing a degree in Biomedical Science at the University of Otago and a Master’s in Clinical Immunology at Victoria University of Wellington.

“I realise the immense responsibility of taking on such important research that may change people’s lives.”

“My choice to go into cancer research was heavily influenced by my mother who passed away of cancer when I was 12. She was truly an inspirational person. She was born in one of the poorest and uninhabitable parts of Northern China where houses do not have toilets or drinking water, sometimes people live in caves. Through her hard work, she became the first person to attend university from her whole village and subsequently became the top scholar of the region. An extraordinary achievement considering the prevalent sexism in rural China,” says Gordon.

“This allowed her to move to a more prosperous region where I was fortunate enough to have been born. She became a great surgeon, as well as an excellent cancer researcher. The irony of the situation isn’t lost on me. Working towards a ‘cure for cancer’ is the ultimate dream for me. I really appreciate the opportunity at the Malaghan Institute.”

Gordon grew up in Hangzhou, China, a city 50 times the population of Wellington. The competition at school was strong.

“With the high population, there was a general acceptance that only students who were exceptionally good at exams would go to university and get a job as a scientist,” says Gordon. “Others were threatened that if they didn’t do better they would be condemned to a life as a factory worker assembling iPhones.”

Lessons were brutally challenging and cut-throat. For Gordon it was difficult to keep up and stay focused.

When his family decided to move to Palmerston North when Gordon was 13, he thought he’d be moving to a tiny village in the middle of nowhere. He was pleasantly surprised to find that as he started school, the world suddenly became his oyster. There was potential to do anything he wanted including going to university to pursue cancer research in his mother’s footsteps.

“This sudden transition from being told my life may amount to assembling iPhones to ‘you can do anything you like’ was truly liberating.”

One of the biggest decisions Gordon has had to make is choosing which field to specialise in to have the biggest impact on cancer research.

“The recent development of mRNA vaccine technology is paving the way for a potential means to overcome cancer. I realise the immense responsibility of taking on such important research that may change people’s lives.”

Related articles

In Focus: Rejuvenating the ageing immune system

17 July 2024

Kia Niwha Leader Fellowship for Malaghan vaccine researcher

6 May 2024

In Focus: Mapping the lung's fight – how the entire organ responds to infection

18 April 2024

Malaghan and National Institutes of Health research receives prestigious award

5 March 2024

In Focus: Tailoring mRNA vaccines for immunocompromised populations

14 December 2023

Scientists identify interferon-gamma as potential SARS-CoV-2 antiviral

13 December 2023