10 May 2023

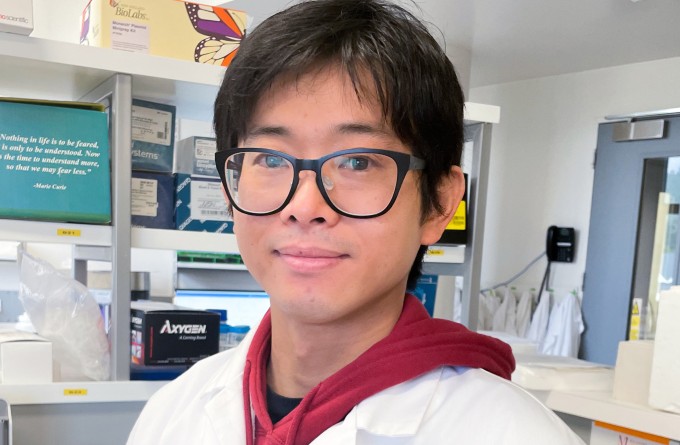

Dr Bibek Yumnam is a Senior Research Officer working in Professor Graham Le Gros’ lab investigating the interplay between parasites and our immune system. He uses his background in conservation of endangered species to offer unique insights into parasites and what they represent to our global ecosystem and health.

The basis of our hookworm therapy programme is the concept that having hookworms in our body may dampen down overactive immune responses typical of allergic and inflammatory diseases.

Specifically, Bibek is working on the Malaghan’s hookworm clinical study to develop the methodology to produce therapeutic hookworms in a safe and standardised way.

“To really understand why we are doing this research we have to look into the life cycle of hookworms in the natural, pre-industrialised world,” says Bibek. “Their life cycle is inextricably intertwined with us humans.”

Human hookworms infect the guts of their hosts where they mate and produce eggs that are released through the faeces.

“Once they are pooed out in the faeces, the eggs hatch into larvae, where they eat bacteria and grow until they are about 0.6mm long,” says Bibek.

In the wild, this stage might occur in tall grass where a bare foot might chance upon the faeces and come into direct contact with the hookworm. It must be at least 20 to 25oC and humid for the hookworm to survive outside the host, which is one of the reasons hookworm infections are so much more prevalent in tropical climates.

“This is the phase where the hookworm needs to find a host or they will die so there are distinct changes in their behaviour including seeking out human body temperature,” says Bibek.

If the hookworm comes into direct contact with the human skin, they release an enzyme that allows them to burrow into the skin and find a small blood vessel. For the human, this might feel like a slight sting.

“The hookworm, still very small, is carried through the blood until it eventually ends up in the tiny blood vessels in our lungs,” says Bibek.

“Here, it gorges itself on blood until it is big enough to make its way up the air passages and it is coughed up. The human host unconsciously swallows it and the hookworm make its way down the digestive tract.”

“Our bodies are an ecosystem and until recently, parasites have always been a part of this ecosystem. We think that the lack of exposure of parasites in industrialised countries may account for the prevalence of conditions such as allergies and asthma,” says Bibek.

During this treacherous journey the hookworm must make its way through the hostile, extremely acidic environment of the stomach and through the vigorous churning of the large intestine. All the while, the hookworm must endure a continuous onslaught from the human immune system which deploys cells called eosinophils to bombard the worm with a cocktail of toxic molecules.

Eventually, the hookworm arrives at the small intestine where it finds itself a cosy crevice in the lining of the small intestine, complete with access to vessels with round-the-clock blood on tap. Without intervention, the hookworm can spend the remainder of its life, anywhere between five to ten years, safely nestled in the lower digestive system.

Often during a hookworm infection, there will be more than one hookworm living in the gut. If there is a male and female, they will spend the remainder of their lives producing eggs which are excreted in the human’s faeces, starting the cycle again for subsequent generations of hookworms.

“Naturally, most people, including many scientists are disgusted by the whole process. We have an innate disgust towards parasites, but our research is challenging the notion that parasites are all bad for us,” says Bibek.

Diseases such as allergies and asthma are overrepresented in populations of industrialised countries. These diseases are caused by our immune systems overreacting to benign substances such as dust or peanuts or even the body’s own cells. The part of the immune system that has been found to overreact, with cells called eosinophils, is the same part of the immune system that attacks parasites.

“Our bodies are an ecosystem and until recently, parasites have always been a part of this ecosystem. We think that the lack of exposure of parasites in industrialised countries may account for the prevalence of conditions such as allergies and asthma,” says Bibek.

“The hookworm has its own, complex immune system which enables the hookworm to live out its life in the small intestine in peace. This tiny immune system has a way of regulating our own immune system, the very part that is overreactive in allergies. This is what we are interested in.”

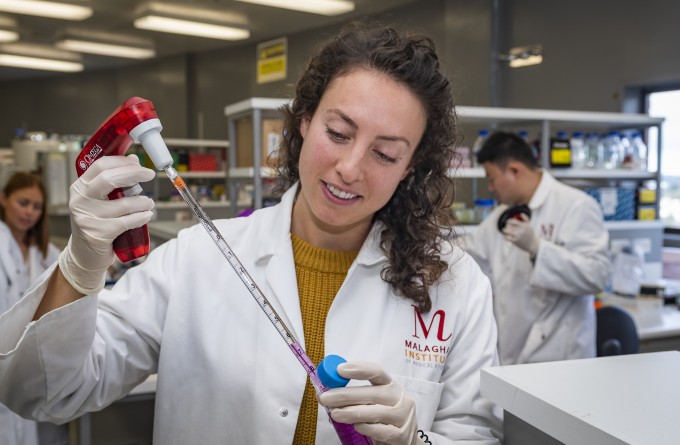

Bibek extracts hookworm eggs from the stools of participants on the Malaghan Institute’s hookworm study, and goes through the painstaking process of cleaning, hatching, cryopreserving, and getting them ready to safely administer to patients.

“These eggs are like gold and there’s a huge amount of muck that we have to go through to get to this gold,” says Bibek.

One key component of making therapeutic grade hookworms is ensuring the hookworm has been cleaned thoroughly.

“We take several steps to separate the hookworm from faeces including using a sieve and centrifuge to separate out the different components and then we use a cell sorter so we can achieve a high level of purification.”

Bibek uses both genetic lab techniques and classical parasitology to identify hookworm species and which developmental stage the worms are in before cryofreezing and storing them ready to be defrosted and administered to participants. A key part of Bibek’s role is developing tightly controlled methods to maximize the reliability of hookworm treatment.

“Making sure the hookworms are clean, at the right phase in the life cycle and even ensuring they are the correct species is very important,” say Bibek.

“It’s an incredibly meticulous process that requires comprehensive and detailed knowledge of the life cycle of the hookworm and how to implement this knowledge practically.”

Prior to working at the Malaghan Institute, Bibek worked on the conservation of endangered species.

“I’ve had experience working with tiger poo and mouse poo so when I was considered for my current role, I knew exactly how to handle human poo as an extension of my previous work,” says Bibek.

“Hookworm research at the Malaghan is important because if we don’t understand the significance of parasites, we might actually be subjecting ourselves to risks related to changing the ecosystem which we have evolved in.”

Bibek is from Manipur, a state in Northeast India bordering Myanmar. The region has a varied landscape with high, jagged, snow-peaked mountains and swathes of lush rainforests teeming with diverse life. Bibek has always had an interest in wildlife and has been passionate about the need to conserve endangered species. After doing his undergraduate and Master’s degrees in Biotechnology, he embarked on a PhD with the Wildlife Institute of India.

“My PhD involved understanding the population genetics of tigers in India. Tigers are a critically endangered species. My research involved collecting samples of faeces and blood to understand the genetic composition of the remaining tiger populations that are localised to national parks all over India,” says Bibek.

Part of Bibek’s fascinating PhD involved trekking through the thick jungle with his team on elephant back to tranquilise tigers to collect their samples.

“I learned to recognise tigers from their stripes and through bioinformatic analysis, I was able to understand the migration and reproductive patterns of the tigers to inform future conservation efforts.”

During this time, Bibek received a Fulbright scholarship to work at the Smithsonian’s Zoological Park in Washington DC. There, he conducted genetic analysis on other endangered species.

Bibek came to New Zealand in 2014 for his wife to pursue her PhD.

“Given my background in conservation, I have a natural inclination to apply findings from our current research at the Malaghan Institute to conservation and vice versa.”

While working at the Smithsonian Zoo, he learned that the Maned Wolves, usually endemic to South America, exhibited symptoms akin to inflammatory bowel disease. Bibek wonders if being kept in an artificial, sanitised environment and being given antibiotics and deworming treatments has played a role in this bizarre phenomenon.

“I think the same is true for humans and the development of allergic and inflammatory conditions. We have enclosed ourselves in self-made artificial, sanitised zoos where we have removed many other life forms that have coevolved with us,” says Bibek.

“Parasites are fascinating because wherever there’s a niche, there will be a parasite exploiting that niche,” says Bibek.

“Hookworm research at the Malaghan is important because if we don’t understand the significance of parasites, we might actually be subjecting ourselves to risks related to changing the ecosystem which we have evolved in.”

Bibek also sees this research as helping us inform how to create an optimal environment for endangered wildlife that depend on us to survive.

“Many endangered species are kept alive with managed conservation programmes that attempt to expand the population of dwindling species. This often involves wiping out any populations of parasites or pathogens using deworming treatments and antibiotics. By taking out the parasites, we are changing the natural habitat of species and we don’t know what effects this might have on their health.” says Bibek.

“Because parasites have coevolved with certain species, we might have to make active efforts to conserve the parasites as well as the species we are trying protect.”

Related articles

New research deepening understanding of elusive eosinophils

27 June 2024

International collaboration finds lipid imbalance in the skin may contribute to inflammatory conditions

24 June 2024

Double doctor: exceptional thesis awarded to Malaghan gastroenterologist

5 June 2024

Location, location, location: study finds where MAIT cells live may determine their role in allergic disease

12 February 2024

Health Research Council to fund clinical study investigating the skin’s role in initiating allergic disease

28 June 2023

Allergic disease research update for Allergy NZ - Dr Kerry Hilligan

30 March 2023