25 January 2022

A collaborative study between the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has found that a vaccine commonly used to treat tuberculosis – BCG – is also effective at preventing lethal infection from COVID-19 in mice when administered intravenously. The study, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, highlights the potential for novel methods for fighting respiratory viruses such as COVID-19 by increasing immune protection in the lungs.

Cartoon rendering of a lung section from a K18-hACE2 mouse inoculated with BCG iv and subsequently infected with SARS-CoV-2. Virus infected cells (blue) are relatively rare and located distally to BCG-induced granulomas (lower right). This is in contrast to sections from SARS-CoV-2 challenged mice that have not been inoculated with BCG iv, where virus staining is more intense and diffuse throughout lung tissue (not shown). Credit: Rose Perry-Gottschalk (NIAID, NIH).

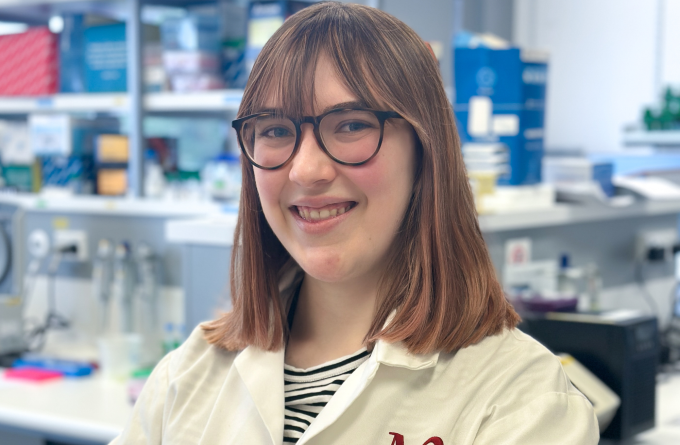

BCG (Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette Guérin) is a live attenuated – or weakened – virus that is used as a vaccine to protect against childhood tuberculosis for over one hundred years. “It’s one of the most widely used vaccines in the world and is administered intradermally (through the skin) within the first few days of life,” says International Research Fellow Dr Kerry Hilligan. Dr Hilligan is part of the Immune Cell Biology team at the Malaghan Institute and has spent the past several years at the NIH in Bethesda, USA researching this vaccine in Dr Alan Sher’s laboratory.

“BCG is particularly intriguing because it appears to stimulate both specific immunity (towards TB) and non-specific immunity against completely unrelated microorganisms, but we don’t fully understand why. It has limited use in New Zealand – because TB is not common here – but is used widely throughout Africa, Asia and South America.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Dr Hilligan and the rest of her team, like many science groups around the world, turned their attention towards the virus and whether their research might be useful in the global fight. Because BCG offers ‘non-specific’ protection against other threats, Dr Hilligan’s team thought it might also help protect people against this novel virus.

Their findings – so far in mice models – suggest that it does, provided BCG is administered in the right way.

“We found that when BCG was administered intravenously it protected our mice from weight loss, disease and death to COVID-19 by accelerating the removal of the virus in the lungs – minimising the amount of damage the virus could cause,” says Dr Hilligan.

“This finding is striking because BCG is completely unrelated to the COVID-19 virus, yet it offers this protection. Importantly, BCG was only effective when administered intravenously – through the veins which stimulate the immune system in the lung, rather than via the skin.”

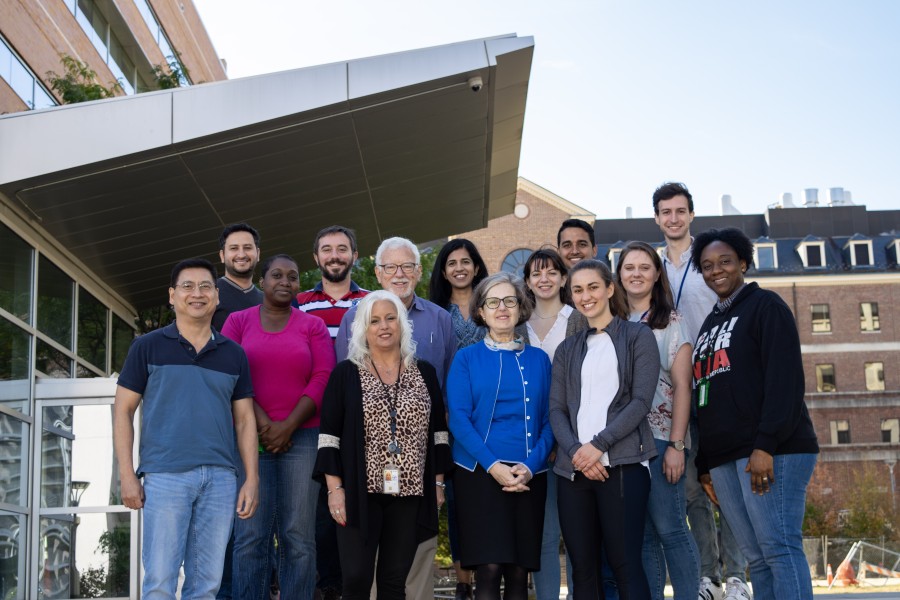

Dr Hilligan with her team in the Dr Alan Sher group at the NIH. Kerry is third from the right, Dr Alan Sher is sixth from the left.

Where a virus enters the host is an important consideration when developing ways to fight it. Like many airborne pathogens, COVID-19 routinely makes first contact with a host via the nasal airway passages, infecting the lungs before spreading out around the body. By priming immune cells in the lung, through potential methods like BCG, scientists can effectively stop the virus ‘at the door’ – before it can do any lasting or lethal damage.

“BCG gives us a powerful model for identifying innate mechanisms of protection within the lung that could be harnessed in the design of future vaccines against respiratory viruses like COVID-19,” says Dr Hilligan.

You can read the full paper here.

Related articles

Winter and the immune system

23 June 2025

New research group taking aim at ageing immunity

20 June 2025

Dr Michelle Linterman: Asking the age-old question

30 April 2025

As easy as breathing: the future of vaccines

31 October 2024

Fever: too hot to handle or the body's first line of defence?

22 August 2024

Rejuvenating the ageing immune system

17 July 2024