12 December 2022

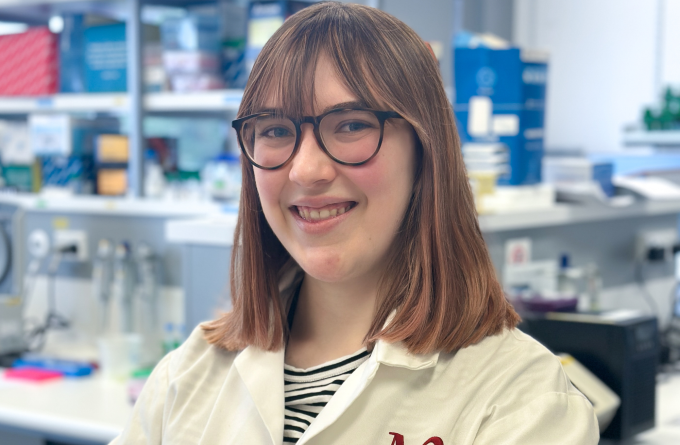

Greta Webb is a PhD student at the Malaghan Institute working to understand the finer details of how allergies develop. Her own experience with asthma has motivated her to uncover the mysteries behind one of the biggest epidemics of the modern age.

“It's like someone has tied a rubber band around your lungs, and no matter how hard you breathe you can't get in enough air,” says Greta.

Greta, like many other New Zealanders, is afflicted with asthma.

“A LOT of people will know how this feels – New Zealand has one of the highest rates of asthma in the world,” says Greta. In fact, one in eight New Zealanders have been diagnosed with asthma.

Allergies and asthma occur when our immune system reacts to molecules in allergens such as dust or peanuts that our body has been conditioned to think is harmful for us. The main type of immune cell that is responsible for this overreaction is a type of T-cell called a type 2 helper T-cell (TH2).

“These TH2 cells evolved to protect us from parasitic infections. However, since industrialised countries such as New Zealand have an absence of parasites, this part of the immune system is thought to overreact to otherwise benign substances,” says Greta.

This partly accounts for why the incidence of allergies and asthma is far greater in industrialised countries compared to developing countries. Other factors that influence the development of allergies and asthma are exposure to pollutants, mould and detergents. Within New Zealand, asthma and allergies disproportionately affect Māori, Pacific peoples and people living in the most deprived areas.

"This fundamental knowledge of how we develop allergic diseases will be pivotal in our understanding of how to make life easier for those who are living with these conditions."

As a child, Greta always wanted to know where her asthma came from and why many of her friends weren’t affected by the same condition. Working in Prof Franca Ronchese’s lab, she is trying to understand exactly this.

“My PhD project is focused on how allergic diseases including asthma develop in the first place. I’m trying to understand the role of a specific molecule called IL-4 in the development of allergies,” says Greta.

IL-4 is a molecule that has been shown to stimulate the differentiation of unspecialised T-cells, called naïve T-cells, into TH2 cells which drive the allergic response.

Allergens are detected by dendritic cells which continually monitor the body for potential threats, picking up foreign molecules and presenting them to other immune cells to stimulate a response.

When a dendritic cell presents a tiny component of an allergen or parasite to the naïve T-cell, it stimulates the T-cell to produce IL-4. This self-produced molecule stimulates the specialisation of the naïve T-cells into TH2 cells. These TH2 cells are what direct the allergic response when a person is exposed to the allergen in the future.

The role of IL-4 in the TH2 response is an old question in immunology that we still don’t have all the answers to. Greta’s research also concerns the role of IL-4 in other immune responses aside from allergies, with data suggesting its role in T-cell division and survival.

“Knowing that you have discovered something new that nobody has seen before is really exciting.”

“This is only part of the puzzle,” says Greta.

“This fundamental knowledge of how we develop allergic diseases will be pivotal in our understanding of how to make life easier for those who are living with these conditions. It may even give us insight on how to prevent this dysregulation of our immune system from happening in the first place.”

Greta grew up in Papakura in South Auckland. She dreamed of being a scientist ever since she was a child.

“I’ve always wanted to know how things work; I’ve always been curious. But being a scientist didn’t feel like a tangible goal until I got to university,” says Greta.

Greta went to the University of Auckland to study biomedical science. She is currently doing her PhD with the University of Otago under the supervision of Professor Ronchese. Three years in, she has six months to go and hopes to continue pursuing research.

“Knowing that you have discovered something new that nobody has seen before is really exciting,” says Greta.

“It makes all of those long days, nights and weekends in the lab, all that time reading, writing and analysing data worth it!”

Related articles

Research sheds new light on the allergic response – and how to disrupt it

5 June 2025

Kjesten Wiig: bringing life-changing treatments to life

27 February 2025

Fighting allergic skin disease at its root

17 December 2024

As easy as breathing: the future of vaccines

31 October 2024

CAR T-cell therapy, the battle of the blood cells

26 September 2024

Fever: too hot to handle or the body's first line of defence?

22 August 2024